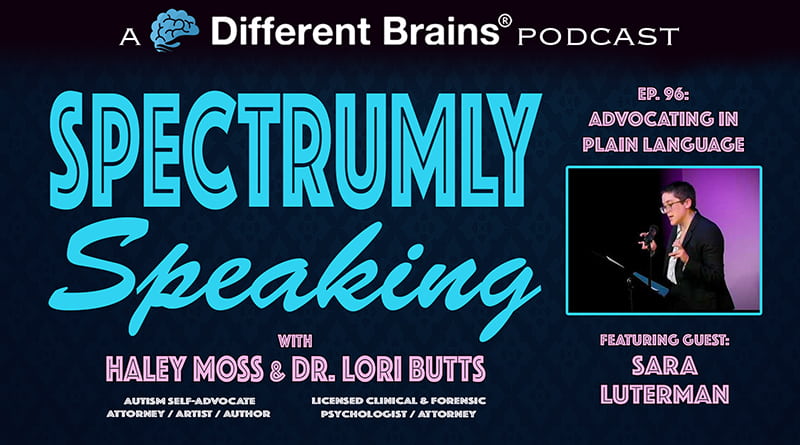

Advocating in Plain Language, with Sara Luterman | Spectrumly Speaking ep. 96

Spectrumly Speaking is also available on: Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | SoundCloud

IN THIS WEEK’S EPISODE:

(37 minutes) In this episode, hosts Haley Moss and Dr. Lori Butts welcome autism self-advocate and writer Sara Luterman. Sara is a freelance writer and editor, with a focus on disability politics, policy, and culture. She writes plain language guides on complex topics, to help make those topics more accessible to people with developmental and intellectual disabilities. Topics have ranged from voting to the US federal budget process and more. You can find her journalism work in The Nation, Vox, and Washington Post, among other outlets.

For more about Sara: twitter.com/slooterman

And be sure to check out her newsletter: NOSletter.substack.com

For more about the book Disability Visibility: First Person Stories from the 21st Century, go to: disabilityvisibilityproject.com/book

And for Sara’s plain language translation, click here.

Spectrumly Speaking is the podcast dedicated to women on the autism spectrum, produced by Different Brains®. Every other week, join our hosts Haley Moss (an autism self-advocate, attorney, artist, and author) and Dr. Lori Butts (a licensed clinical and forensic psychologist, and licensed attorney) as they discuss topics and news stories, share personal stories, and interview some of the most fascinating voices from the autism community.

For more about Haley, check out her website: haleymoss.net And look for her on Twitter: twitter.com/haleymossart For more about Dr. Butts, check out her website: cfiexperts.com

Have a question or story for us? E-mail us at SpectrumlySpeaking@gmail.com

CLICK HERE FOR PREVIOUS EPISODES

EPISODE TRANSCRIPTION:

HALEY MOSS (HM): Hello and welcome to Spectrumly Speaking. I am Haley Moss, an attorney, author, artist, an autistic self-advocate, and today I am joined here by

LORI BUTTS (LB): Hi, I’m Dr. Lori Butts. I’m an attorney and a psychologist.

HM: How is your week going?

LB: Good, good. Lots of my plate so just kind of organized and try to get everything done. How about you?

HM: Good. Kind of tired of Zoom for now. I spent most of the week in zoom seminars and got to go to this really cool workshop for the last couple days, which was really informative, and they had us in like small discussion groups. We talked about inclusion in law school, so people with disabilities, law students with disabilities, and just talking with deans, other attorneys, and students. It was just really interesting seeing where that conversation is going and hopefully change will happen.

LB: Great.

HM: So, it was really cool getting to learn from everybody and they were absolutely wonderful. All the speakers. So, they had some professors, they had some students, they had some recent grads, it was just a really great mix of people.

LB: Wow. Was it the Florida bar that did it?

HM: It was the National Disabled Law Students Association, the people who administer the LSAT, and the Koala Center at Loyola.

LB: Wow, that’s awesome.

HM: That’s a really great thing for people and I hope to see more stuff like that.

LB: Absolutely, yeah well, you’re a leader in that area.

HM: That was the highlight of my lead attending there. Just to learn from people, take notes and see what the next generation is doing cause somehow, I’m no longer in school.

LB: [Laughs] You’re still part of the next Generation.

HM: I know. I feel like it whenever I go to like a young lawyers division meeting because apparently there was only two people that were born after 1990.

LB: [Laughs]

HM: And keep in mind that young lawyer’s division their idea of young has anyone like under thirty-six during their first five years of practice.

LB: I think anyone in their forties are young. [Laughs]

HM: So, I’m sitting there like definition of young like I am legit young here.

LB: Yes, you are.

HM: And on this board of like sixty we find out that there’s only two people born after 1990.

LB: Wow. Yeah, so they need you and you’ve got a great perspective and great input. That’s wonderful that you’re doing that.

HM: I’m very excited to get to serve on a couple committee so making sure that disabled lawyers are heard on diversity and also being part of that mental health and wellness committee to make sure that everybody is included and it’s not just cause you know how all the stigma free initiatives are with like lawyers.

LB: Yes.

HM: But thankfully we’re not spending the whole day talking about lawyers and law students.

LB: [Laughs] No.

HM: I think we have a lot of really cool stuff going on and what’s really great is by the time people are listening to this we will be celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

LB: Great.

HM: And to help bring in ADA 30 we have a really great guest and I’m really excited to introduce you to her — are you ready?

LB: I’m ready.

HM: Our Guest today is Sara Luterman. Sara is a freelance writer and editor with a focus on disability, politics, policy, and culture. She writes plain language guides on complex topics to help make those topics more accessible to people with developmental and intellectual disabilities. Topics have ranged from voting to the US federal budget process and more. You could find her journalism work in the nation Vox and Washington Post, among other outlets. Welcome to the show.

SARA LUTERMAN (SL): Hi, thanks for having me. I’m excited to be here.

HM: Thank you for joining us. So, as we always like to begin to help get people some background. Would you like to share with us how you became involved with the autism community?

SL: Yes, so like a lot of autistic people assigned female at birth. I didn’t get diagnosed when I was younger. I didn’t get diagnosed until after I’d finished grad school and then it was entering the job market and I just couldn’t get a job. My resume was fine and then I’d get to the interview stage and then it would just never go anywhere and so about a year into that, my mom read this book called Look Me in the Eye by John Elder Robison and she was like holy heck that’s Sara so she suggested that I get evaluated. I’m very grateful that I had my parents support to do it and it changed my life. I guess for a long time I thought I was like somehow just like this uniquely broken thing that had crawled out from under a rock and finding out that other people like me exist and that I wasn’t like bad or wrong was really powerful for me. I still struggle with employment but at least I kind of understand why and what’s going on and it definitely makes my life a lot easier and happier.

LB: What got you interested in writing, especially plain language writing?

SL: I’ve always been interested in writing. I majored in writing in college. My graduate degree is an MFA in creative writing. I originally thought maybe I wanted to go into Academia, but I really sort of fell in love with writing. Writing is communication like I became very frustrated with academic writing because started working with other people of the intellectual and developmental disability community and I quickly realized that language that doesn’t communicate with everyone has really limited utility. So, I originally got interested in it because I wanted to be able to help other people advocate because when everything is old, jargon, and wrapped up in super special secret academic language it’s a lot harder for people to advocate for themselves. It’s an easy problem to fix.

HM: Definitely and something that I thought was really cool as I saw that you translated the disability visibility Anthology into plain language and it’s something that I’ve been starting to pour through both reading the Anthology and the plain language translation so can you share a little bit about the Anthology and you’re working putting it into plain language for those who haven’t had the chance to read or heard about it yet.

SL: Absolutely. So, the disability visibility Anthology is edited by Alice Wang, who’s really amazing disability rights Advocate and activist who lives in California. it’s a collection of first-person stories from all kinds of different people in the disability Community with all different kinds of disabilities. Some of the story like some of the essays are very academic, some of them are very complex, some of them are emotionally complex. A lot of them deal with difficult subject matter and I think that it gives a really good overview of the diversity that exists within the disability Community. It’s by Elisa Thompson, who’s another disability rights activist, started this hashtag on Twitter called disability to White and I think that one of the best things about the disability visibility Anthology is that it sort of upends that idea and makes sure that all kinds of voices are included. In terms of like all kinds of voices are included, Alice actually reached out to me to do with language translation of her book and I don’t think anyone’s ever done anything like this before to be completely honest. I did a lot of when she asked me, I was really intrigued because it sounded like a really challenging and interesting project. I looked into like the kinds of like if there were any equivalents, so there’s a lot of us nonprofits that do plain language translations of materials. That’s sort of a growing area in accessibility. So for example, I’ve wrote the template of Voting Rights toolkit for the autistic self-advocacy network, which explains voting and whether people under guardianship disabilities are allowed to vote in every state at a 4th grade reading level and so but that’s a lot more straightforward than like creative nonfiction because you’re just sort of all you have to communicate is the idea. You don’t have to try to preserve off your voice or any of the uniqueness of the of the original writing. Basically, I was just taking legalese that some of the lawyers who work at the autistic self-advocacy Network gave me and turning it into something comprehensible. So, the disability visibility project anthology was a whole new thing. There are plain language translations sort of but they’re usually called young reader editions and they do like bump down the reading level on fiction and creative nonfiction but they also tend to sort of change the age appropriateness and I don’t think that that’s an acceptable thing to do when writing for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities because they’re adults. Like, adults with intellectual disabilities are adults and so changing the content to be more like kid-friendly is an inappropriate thing to do so that that also made this project very distinct from Young reader Editions.

HM: I think that’s a really important distinction that you bring up that it’s still not necessarily making the subject matter easier to digest, in fact like that is not for kids that it’s still at people’s intellectual disabilities are absolutely adults and I was reading your translation of Harriet McBryde Johnson unspeakable conversations and I thought it was really well done and how you were able still get across the points of debating a Princeton Professor about like quality of life and write in right to life and things like that to that you were able to break it down in a way that was accessible.

SL: I’m very proud of that piece. I think it’s one of my favorites in the Anthology and I really hope that it helps people get engaged because it seems like a lot of the disability rights community is very exclusionary towards people with intellectual disabilities or people with low literacy, because a lot of the stuff that makes up our movement is extremely online and a lot of people in group homes don’t even have access to the internet and it’s extremely text heavy. There’s a lot of like crypt theory and that’s just not something that most people live alone people with intellectual disabilities have an easy time connecting with and I don’t think that’s a good thing for a movement that’s ostensibly supposed to advance rights.

LB: I think it’s fascinating that the way that you speak about what you do, you kind of downplay it and I think it’s an amazing skill to be able to digest complex issues and make them understandable. I don’t think I have that skill whatsoever and I think that that’s an amazing ability of what you’re doing, so I just noticed that you were just kind of saying you know, well I kind of just read it and make it understandable, just kind of it’s a very difficult and challenging task.

SL: Oh, no. I want to be clear. I don’t just read it and make it readable like that’s it. There’s a whole method that I developed that anyone can do actually and I’d really strongly I would love if other people crypt the method that I just made. I actually described it in the introduction to the plain language edition of the disability visibility project. So, the way that I do this is so to start off, there are reading levels. I’m going to say that the reading level works is that it’s described in reading levels even though that’s not necessarily. Like I said, adults with intellectual disabilities are adults. It feels weird saying like you know 4th grade reading level or 5th grade reading level when you’re talking about something that you’re writing for an adult, but that’s just the language that goes with the scales that exist. So, there are websites online that can give you a reading level on a piece of text. So, usually when I’m translating a piece of text, I start out by running it through one of those engines and then I just get a feel for like what level it’s on or starting off. Most of the essays in the anthology were rounds of 12th or 13th grade reading level. I know that 13th grade isn’t a thing in real life, but it is in readability-score-land. [laughs]

HM: The more you know.

SL: Yeah. So then after I evaluate where in the writing already is, I start trying to lower the reading level. So, in order to do that, you need to shorten sentences, remove passive voice as much as possible. So, you want to front load sentences so that the subject is at the beginning. Try to remove as many extraneous clauses as possible and usually through that method I’m able to get it down to around 4th or 5th grade reading level. The other thing about readability score is that the complexity of words matters. So, the way that I work on word complexity is through a combination of simple English Wikipedia which is a really great resource and this tool that actually wasn’t designed for accessibility work called up go or six. So, up go or six is actually based on a webcomic by Randall Monroe called XKCD and Randall Monroe made this one comic called up go or five that explains how the Saturn V rocket works using only the most common thousand words in the English language, and it’s a really great comic I really recommend people look it up. So, a fan of the comic made a word engine called up go or five that only allows you to use the one thousand most common words in the English language and if any words that aren’t, it’ll pull them out. So, that’s a little bit too restrictive.

So, there’s a new engine that someone else made called up go or six. An up go or six color codes the words of a text that you put into it based on how common they are, and it actually pulls information from simple English Wikipedia because simple English Wikipedia tries to keep it to the most common thousand words in the English language as humanly possible. So, of course, its color coded so that the easiest words are green. Or the most common words are green, and the least common words are red and then they started this great in between. It’s not really accessible to people who are color-blind, but it also wasn’t designed as an accessibility tools, so I understand that the person who created it wasn’t really thinking about that. So, the great thing about that tool is that you can kind of pick the point where you want to cut off like how common. You can sort of pick your own point for cutting off language instead of having to cut it off at the most common one thousand words. The average adult person has about twenty-two thousand words in their vocabulary in English, so I did my cutoff for this anthology at three-thousand. I admit I think it’s kind of arbitrary, but it just seems like a good number. It seemed like a number that encompassed the most commonly understood words because there are some words that I think are more commonly understood that don’t make it in under those one thousand line so then after I run it through a Gore six, I read it out loud. So they’ve already simplified the sentence structure and I’ve replaced all of the words that I can with easier words with the theory that like the likely the more common the word is, the more likely it is to be understood, and then I read it out loud, and that’s actually a really good test because if it doesn’t make sense when you read it out loud it probably doesn’t make sense.

Then there’s one other step that I do on top of everything else that probably wouldn’t need to be done for most plain language materials, but this is specifically for people with intellectual developmental disabilities where I try to remove as much figurative language as possible because figurative language can get really confusing for people, especially with autistic people. When you have creative nonfiction or creative fiction is a huge problem because that sort of figurative language is a big part of the author’s voice, so learning how to balance that was definitely a work-in-progress. I don’t know if I was entirely successful in every single essay in disability visibility project, but I did my absolute best and I’m really proud of the work that was produced. I’m sorry that’s all really overly complicated I can’t magically like make things plain language like I have a whole process that I used to do it.

HM: I think that’s good to know.

LB: I think that you need to be in every legislative single piece of legislation that comes out that you need to be on staff to make it make sense because I mean it’s just I could speak to you all day about this because I think it’s wonderful and fascinating I think it’s so important that that people understand laws like in Florida and I’m going off topic I know but it is in Florida when we have these amendments on our voting.

HM: The constitutional Amendments?

LB: Constitutional Amendments and I’m a lawyer and I can’t even answer.

HM: I know. I have to go through whoever decides to translate them and read all the newspaper covers cause it’s the closest thing to making sense I’ll get.

LB: And we’re both lawyers.

HM: I shouldn’t have to trust anything that the local newspaper has to say about the amendments and understand what they even are.

LB: So, Sara, we have lots of lots of opportunities for you all across to help to help do your magic and make legislation accessible to everyone across this nation because I think it’s very important, but anyway.

SL: Can you imagine if we plain language of SCOTUS decisions?

LB: Exactly! Exactly, it’d be great. Anyway. So, it’s a total 180 but Sara, from your perspective, can you talk about the challenges of highlighting disability issues during this Covid pandemic?

SL: This touches more on the journalism side of my work, which is my passion. It’s unfortunately not where the money is but it is my passion and It’s been difficult for a lot of reasons. People with intellectual and developmental disabilities in particular are largely segregated from our society. While most no longer live in large institutional settings, a lot of group homes really function as many institutions. There’s this thing called the burrito test that Dave Hingsburger developed to determine if someone belongs in an institution and the burrito test is if you want can you wake up at 3 in the morning and go microwave a burrito. If the answer is no, then the setting is institutional, and a lot of group homes do not pass the burrito test. So, like you have people who are like largely hidden and live these very restricted lives and so it’s really difficult to get people to see what’s happening or to understand why it’s important because these are not people that most people see every day because of the equitable way that our society and our Disability Services System is designed. So, when I’ve been pitching stories about this kind of thing, I really tried to stress how important it is that the stories of people that our society rarely pays attention to get told. I’m also a huge fan of Joe Shapiro’s work and at NPR he has done some absolutely stellar investigative work on these particular issues since the epidemic started.

LB: Wow it’s important stuff, really important stuff.

HM: Absolutely and I know that I really appreciate the work that you do, and I remember reading your piece in the nation about immunocompromising disabled kids and it was something that really stuck with me. So, you do really amazing work and I love that writing is your passion so I’m sure we have listeners who also have similar passions and what advice do you have for them if they want to get into writing.

SL: I want to be honest. I don’t know if I’m the best person to give that advice because I’m self-employed and barely make any money. [Laughs] I mentioned at the beginning of the episode that I sort of struggled to get into traditional employment and that never really changed. Unfortunately, I’m thirty and still don’t have like a normal people job but I think the most important thing is to just keep working at it. You get rejected a lot when you’re when you’re writing like a lot a lot of most of the time editors will not respond to your pitch. They won’t tell you got rejected you just don’t hear back from them and so you have to be very self-motivated and really confident that the stories you want to tell him the things you have to say or important and you have to keep for the pushing and advocating for your own voice. I really like, this is a little goofy but I kind of have as my Mantra when I when I’m pitching and writing like Dory from Finding Nemo where she’s like just keep swimming just keep swimming just keep swimming and that’s what I feel about writing cause you’ll get rejected like a million times but that one time someone says yes, you’re in business.

HM: I think that’s actually really good is that you’re highlighting the reality of it because I think a lot of people feel like writing is super idealistic and everything just kind of works out.

SL: [Laughs] Oh no. That would be really nice though. A hundred percent.

HM: So, if people want to follow your work how can I find out more or see what else you’re up to?

SL: So, I’m pretty active on Twitter. That’s like at SLutterman. You put two O’s instead of instead of the U because that’s how my name is pronounced and I have a Weekly subscription newsletter that actually is a significant chunk of my income using this platform called substack and it’s called the NOS letter so it’s like NOS letter dot Sub stack.com and I do a weekly Roundup of all of the big disability stories of the week plus an original essay or original reporting from myself and then I try to end it on a positive note which is actually Haley’s suggestion and I stuck with it cause I think it’s great to sort of leave something uplifting in the newsletter every week while the world is collapsing. Sometimes the positive thing is the article I read that I think it’s funny. I think I put it in like a recipe one time for matzo brei during Passover because I was feeling homesick cause I couldn’t go visit. yeah so it’s, I really would love people to subscribe to my newsletter and that’s probably the best way to follow my work.

HM: I love getting the newsletter every week and I remember when the beginning with the positive note we had lots of trains.

SL: Oh, so many trains. The wholesome train content is always important hopefully we will get more in the future. There will always be more wholesome train content. I just got to mix it up cause I not all of my readers are on the spectrum.

HM: We want to talk about ADA 30 a little bit and also just greater accessibility language and all that good stuff that we were talking about earlier as well just keep that conversation going.

LB: I think that this is a really important point. I just I mean I can’t stress it enough that you know accessibility with reading and with understanding things is just a basic fundamental right, especially in this crazy culture of misinformation and you know not knowing what information is accurate and I mean to be able to process information yourself by just reading is just crucial. I don’t know more to say about that. I think that the work that Sarah does is it’s really important.

SL: I do want to emphasize that I didn’t invent the plain language or easy agreed translation. Actually, if any listeners are interested in like getting those kinds of translations, the best people to reach out to our at the autistic self-advocacy Network who sometimes contract out to me or Green Mountain self-advocates. Both of them make plain language translations of all kinds of things. It’s just that those materials are normally policy related whereas the disability visibility book is a book.

HM: I keep thinking back to what you said earlier about how it’s not just making young readers Edition, because I’ve been seeing since I’ve been seeing young readers edition of certain adult books come out more often and I personally like young reader stuff sometimes they make like I love young adult fiction for instance a lot and I think like certain other things, like there’s a place for this to be translated, kind of I think a lot about even like stand for the beginning I know there was a remix version that was meant for young adult readers and at the same time like I hope it doesn’t take away from what is meant for adults because it’s still adult topics and adult themes and things like that too so I’m very curious what that turned out to be like. So, I think that it’s very important just to keep it to obviously make sure things that are for people with intellectual disabilities are also for adults too.

SL: It’s not just for adults with intellectual disabilities. I mean you’ll see, if you like watch shows with subtitles on Netflix or other platforms, they’ll censor the swears, like they won’t say exactly what the people on screen are saying. Like deaf people are like somehow not able to handle that kind of language like it’s not just people intellectual disabilities that get infantilized that way, like, it’s people with disabilities in general and it’s really frustrating.

HM: I didn’t even realize that they sensor the swear words in subtitles.

LB: Yeah, I didn’t either.

HM: So, these are things that should definitely be changing going for I think you should think that you’re definitely changing going forward but how do we get that conversation started beyond just us.

LB: Right.

HM: I think that’s the million-dollar question.

LB: Yeah, exactly.

SL: What I think people should in plain language translation to any grants that they’re doing. I think that they need to budget for that kind of accessibility. There’s like a saying in nonprofit lands that budgets are statements of values, and so I think that it’s really important for scientific researchers for people to do any kind of political advocacy work like you need to budget for a plain language translation because your work should be accessible, especially if you’re working an intellectual and developmental disability around your work needs to be accessible to the people you’re ostensibly doing the advocacy for.

LB: How about just across the board everyone just rights in plain English? Why do we have to make it so why doesn’t even have to be complicated for anybody? I just think that what you’re making the same point whether or not you write it in fancy huge words or in plain language and I think that it’s either when I went to law school there was a big push for plain language lawyer-ing on my I don’t know what it is now I mean, writing contracts like a real estate contract just like simple everyday transactions.

SL: I think that would help the courts out too and then we’d have a lot less frivolous litigation but that’s a whole other rabbit hole but yes, I do think most legal things should be in plain language.

LB: Right, I mean you look at the user, you know everyone always laughs about

SL: The terms of service?

LB: Exactly, exactly. [Laughs]

SL: Just tell me if you’re going to take my first-born child.

LB: Right! [Laughs].

SL: Like just let me know. just let me know.

LB: Like online survey. Just let me know and bullet points. Just do bullet points. Anyway.

SL: I think it would be I still think that having court decisions in plain language would be really nice, especially because those are available to the public

LB: Right, but I mean just buying a car, you know getting an apartment, you know these transactions that people have to participate in on an everyday basis, there’s no it’s not necessary to have all this superfluous wording and plain language works and it gets people on the same page.

SL: I do want to say that I think there is like a place for complexity and that there’s Arden complexity creative writing.

LB: Right.

SL: When it comes to writing, the word choice is very specific and actually that was one of the biggest anxieties I had about translating disability visibility project is that like all of the words are chosen for very specific reasons, so anytime I change anything I have to think like how much does that detract from the author’s intention, how much just that detract from the mood they were trying to build, how much does that detract from their voice, it think complexity can be very beautiful but I just think it doesn’t belong in policy materials. [Laughs]

HM: I kind of think that it’s a big distinction too.

LB: Exactly, exactly.

HM: So I think that’s something we should definitely be keeping in mind as we go forward and for anyone who does work in policy or anything of that nature like try to make sure that your materials are accessible.

SL: Oh, there is one more thing I want to add about the process that I use. So, I wasn’t able to do this with Alice’s book unfortunately because of because of the Covid crisis, but I really important part of making sure your language is accessible is focus grouping it. So, people first chapter of switcher like self-advocacy groups for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, you can actually contract them to help review the plain language materials that you have to make sure they actually make sense.

LB: Oh wow. That’s great.

SL: I really strongly recommend doing that but it was unfortunately not possible because of the pandemic because just getting people online is a lot harder than like getting everybody in a group to sit down and talk, but it is it is a really important part of the process.

HM: I think we learned a lot today I don’t know about you Dr. Butts, but I feel like we just learned a lot.

LB: We did we did and it’s obviously tapped into something and I have strong feelings about it because I just think everybody that you know signs up for health insurance or just needs a similar decision in their life, they need to be able to understand what they’re agreeing to and there’s a there’s a clear path to being able to do that without having to be difficult for people with dyslexia or people with learning disabilities or any kind of issue.

SL: I’m sorry for info dumping this by the way it’s just something I’m really excited about.

HM: Oh my god. Please don’t apologize because its stuff that we need to know.

LB: Exactly exactly.

HM: I’m sitting here like I wish that I was taking notes. Hopefully, this will be available for everyone and we’ll get the listen and hopefully get a transcript as well then, we can take lots of notes. Exactly. So I think that’s a really great note to end on especially because we are learning a lot and this is again a friendly a friendly place to get to learn these things and have these conversations, so thank you again Sarah. If you want to follow Sarah’s work be sure to check her out on Twitter at Sluterman with the two o’s or subscribe to the NOS letter. I personally love getting the NOS letter on Mondays so that’s just my extra plug in there too and be sure to also check out different brains.org and check out their Twitter and Instagram at diff brains and look for them on Facebook too. If you’re looking for me, you can find me on Facebook Twitter and Instagram at Haley Moss art or a HaleyMoss.net.

LB: I can be found at CFIexperts.com. Please be sure to subscribe and read us on iTunes and don’t hesitate to send questions to spectrumlyspeaking@gmail.com. Let’s keep the conversation going.

Spectrumly Speaking is the podcast dedicated to women on the autism spectrum, produced by Different Brains®. Every other week, join our hosts Haley Moss (an autism self-advocate, attorney, artist, and author) and Dr. Lori Butts (a licensed clinical and forensic psychologist, and licensed attorney) as they discuss topics and news stories, share personal stories, and interview some of the most fascinating voices from the autism community.