Dyslexia & Creativity: Chuck Close’s Micro-Uniting and Universal Design

By Ken Gobbo

Exploring Dyslexia and Creativity

My interest in a possible connection between dyslexia and creativity began with observations of some of my students and the ways that they learned best. For many years I taught psychology at Landmark College in Putney, Vermont. Landmark is a school that serves students who learn differently. The student population includes many with dyslexia. I noticed that some of my dyslexic students would take different approaches to understanding the abstract theoretical concepts covered in the Psychology classes I taught. Some would organize ideas visually using diagrams to categorize or sequence concepts. Others would rely on examples of events in their own lives or lives of their friends to understand concepts. I thought perhaps that there was something about the challenges faced by individuals who struggle with language because of dyslexia that motivates them to find new and creative ways to understand concepts that are ordinarily shared through language.

Artists with dyslexia

As I continued to observe these tendencies in my students, I started to do some informal research on possible connections between dyslexia and creativity and came upon a handful of artists whose work I already admired. I found that three of these artists had spoken publicly about their experience with dyslexia. Robert Rauschenberg, Chuck Close, and Charles Ray have discussed the impact dyslexia has had on their work as artists. All struggled in school as children, adolescents, and young adults during a time when little was understood by teachers about learning differences like dyslexia.

During the 1950’s and 60’s students like the three individuals mentioned here were often seen as lazy, non-compliant, or just not too bright. The three artists mentioned not only were successful in colleges and universities as art students, but they went on to become leaders in their respective fields. They were able to think “outside the box” and go beyond current trends and successfully create new styles of expression

Chuck Close’s challenges

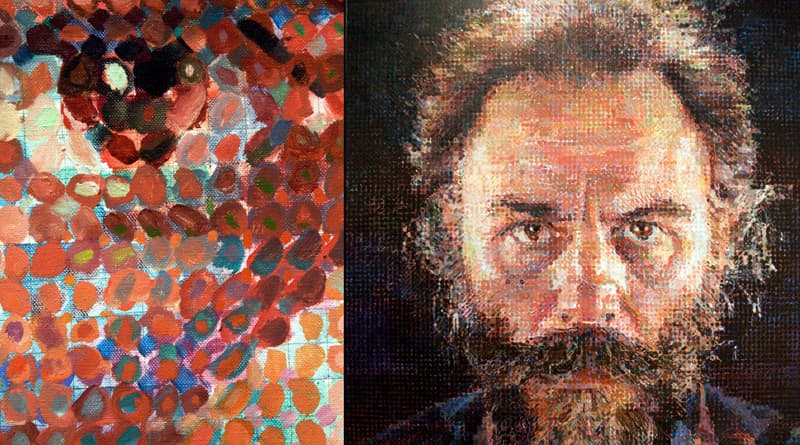

Of the three artists mentioned here, Chuck Close was perhaps the most challenged by his life circumstances. Close not only struggled with dyslexia, but he also experienced prosopagnosia, a neurological difference that makes it difficult to recognize faces. Later in life he experienced a spinal artery collapse which left him paralyzed. He met all these challenges head on. He developed strategies to overcome the difficulties he was presented with. The young man who was advised buy his guidance counselors in school to consider going into auto body work went on to become one of the most well-known portrait artists in the world. As a young artist he broke away from the prevailing trend of abstract expressionism and moved to a painting style which employed breaking an image of his subject down into small parts and reproducing them on the canvas. Eventually these small parts would become very small boxes with geometric patterns in them that would culminate in a very large image of his subject.

Micro-uniting

The main idea underpinning his work is breaking down a visual depiction into the smallest parts possible and then reassembling them into the desired image. In a 2012 CBS This Morning television interview he explained, “If you are overwhelmed by the size of a problem, break it down into mini bite sized pieces.” In a conversation with art critic Judd Tully the artist explained how he prepared for exams when he was a struggling student in high school. Close would sit in the bathtub filled with warm water in the dark. He would shine his flashlight on the text he was studying. He would break the important concepts he was studying down to their smallest elements. Then he would create visual images or sentences to remind him of the elements so he could reconstruct and remember them later. This took a long time, but it worked for him. Later he would use a strategy like the one he used to overcome some of the struggles he faced as a student with dyslexia in his approach to portraiture. Prosopagnosia prevented him from recognizing faces of people he knew, but he could reduce them to smaller elements and recombine them into a portrait. As a student he would also convince teachers to allow him to accept alternative visual explanations of work rather than written ones. For example, he would illustrate poems or map out historical events. As a matter of necessity, on his own he developed examples of micro-uniting and universal design. Micro-uniting is breaking down a concept into its smallest parts and teaching or learning one part at a time. It helps students to connect concepts and stay focused. Universal design allows students to engage with content in a variety of ways and to also demonstrate their learning in a variety of ways.

No doubt Chuck Close’s approach to breaking up large problems into smaller manageable units inspired him to flatten out faces on very large canvases and break them down in to small elements that combine into exceptional works of portraiture. His works of painting and photography depicting friends, fellow artists, musicians and even presidents hang in galleries and museums throughout the world. Each one is a product of solving problems through persistence, hard work, time, and taking a situation and breaking down into smaller parts and managing it.

For more stories like this, take a look at Ken Gobbo’s book Dyslexia and Creativity: Divers Minds, which offers insights into the connections between dyslexia and creativity and illustrates them through the lives of well-known artists and writers.

Ken Gobbo is Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Landmark College, Putney Vermont, USA. He has published numerous articles on learning differences, neurodiversity, and teaching in peer-reviewed journals. His book Dyslexia and Creativity: Divers Minds offers insights into the connections between dyslexia and creativity and illustrates them through the lives of well-known artists and writers.