Toxic Stress and its Impact on Children

By Dr. N’Quavah Velazquez

Toxic stress is a growing concern for children who live in capricious environments and receive substantial care from a loving adult. In a healthy environment, children are powerful. From birth to five years of age is one of the most fertile and ripe periods for growth and development. This window is “a time of rapid and dramatic postnatal brain development and of fundamental acquisition of cognitive development” (Rosales, Reznick and Zeisel, 2013).

Positive experiences during the early critical period in child development contribute to the foundation of a viable and flourishing society (Center on the Developing Child, 2007). However, toxic stress can derail this fertile and ripe period of child development. Hence, the question this discussion will address is twofold: (1) What is toxic stress and how does it compare to other forms of stress? and (2) What are some impairments of toxic stress in early childhood?

There are different types of stress. For example, positive stress is a short-lived stress. It is a normal and necessary part of healthy living. Children can usually adjust to these experiences without harm. Another type of stress is tolerable stress. In this case, the potential of stress to be damaging is high but is not ongoing. Therefore, the brain has a chance to recover from tolerable stress. On the other hand, toxic stress is pervasive. Note what one body of researchers said:

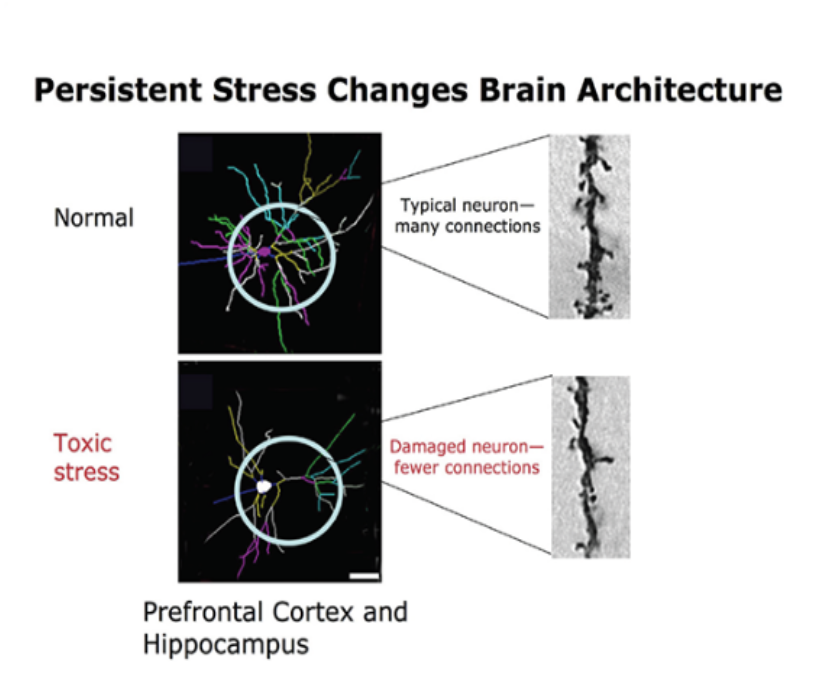

“Toxic stress refers to strong, frequent, or prolonged activation of the body’s stress management system. Stressful events that are chronic, uncontrollable, and/or experienced without children having access to support from caring adults tend to provoke these types of toxic stress responses. Studies indicate that toxic stress can have an adverse impact on brain architecture. In the extreme, such as in cases of severe, chronic abuse, especially during early, sensitive periods of brain development, the regions of the brain involved in fear, anxiety, and impulsive responses may overproduce neural connections while those regions dedicated to reasoning, planning, and behavioral control may produce fewer neural connections … Therefore, the stress response system activates more frequently and for longer periods than is necessary … This wear and tear increases the risk of stress-related physical and mental illness later in life.” (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2014 p2).

Hence, toxic stress has a negative impact on children in a profound manner as the balance of this discussion shows.

Figure 1 illustrates that toxic stress weakens development of neural architecture in critical areas of a child’s brain associated with learning and behavior in school.

Figure 1. Toxic Stress Alters Neural Architecture

Source: Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2007).

In addition, the following are two videos from researchers at the Center of the

Developing Child at Harvard University. The first video shows the impact of toxic stress on neural development whereas, in the second video, researchers expand their discussion to show two ways to potentially intervene with toxic stress in children: (1) early identification of at risk populations; and (2) high quality preschools.

Figure 2. The Impact of Toxic Stress on Neural Development

Source: Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2011, September 29).

.

.

.

Figure 3. Toxic Stress on Neural Development in Children and Suggested Interventions

Source: Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2011, January 11).

Given the impact of immediate and long-term toxic stress on children and society, it

is imperative that ongoing research provides reliable and valid instruments to identify efficacious intervention methods for toxic stress, and reverse under-develop neural brain architecture in children attributed to such stress. It is also essential that educators, clinicians and those that provide children’s services keep abreast with the growing body of knowledge on toxic stress and its impact on children (Skonkoff, 2011; Walkley and Cox, 2013). In these ways, we may help more children flourish as they grow and develop as adults in our society.

.

.

Dr. N’Quavah Velazquez, Achievement Heights Academy

Visit our website at achievementheights.org and follow us on: facebook.com/achievementheights | twitter.com/achievementhgts | linkedin.com/in/achievementheights

References

Center on the Developing Child (2007). InBrief. The science of early childhood development. Retrieved on October 16, 2016 from website at http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/

Center on the Developing Child (2007). InBrief. The impact of early adversity on children’s development. Retrieved on October 28, 2016 from website at http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-the-impact-of-early- adversity-on-childrens-development-video/

Center on the Developing Child (2007). Early Childhood Program Evaluations: A Decision- Maker’s Guide. Retrieved on October 30, 2016 from website at www.developingchild.harvard.edu

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2016). From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts: A Science-Based Approach to Building a More Promising Future for Young Children and Families. Retrieved on October 30, 2016 from website at www.developingchild.harvard.edu

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2004). Young Children Develop in an Environment of Relationships: Working Paper No. 1. Retrieved on October 30, 2016 from website at www.developingchild.harvard.edu

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2005/2014). Excessive Stress Disrupts the Architecture of the Developing Brain: Working Paper 3. Updated Edition. pp. 1- 12. Retrieved on October 16, 2016 from website at http://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/wp3/

Rosales, F.J., Reznick, J. S. and Zeisel, S.H. (2009). Understanding the role of nutrition in the brain and behavioral development of toddlers and preschool children: identifying and addressing methodological barriers. Journal of Nutritional Neuroscience, (12)5, pp. 190-202. Retrieved on October 16, 2016 from website at http://dx.doi.org/10.1179/147683009X423454

Skonkoff, J.P. (2011, October 28). Protecting brains, not simply stimulating minds.

Education Forum: Science Magazine: American Association for the Advancement of Science, (333)6045, pp. 982-983. Retrieved on October 30, 2016 from website at http://science.sciencemag.org/content/333/6045/982

Walkley, M. & Cox, T. L. (2013, May 8). Building trauma-informed schools and communities.

Children and Schools: A Journal of the National Association of Social Workers, (2)35, pp. 123-126. Retrieved on October 30, 2016 from website at http://cs.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2013/04/23/cs.cdt007.short# doi:10.1093/c/cdt007

Dr. N’Quavah Velazquez is a veteran educator with more than 20 years of experience. Moreover, as a published Ivy League medical and education researcher, she is adept at applying proven research strategies to decision-making and efficacious practice. She is the CEO and Executive Director of Achievement Heights Academy, Inc. (AHA), a 501(c)(3) nonprofit and nonsectarian organization that Dr. Velazquez also found. In addition, a dedicated governing board of directors and an esteemed advisory board are part of the AHA leadership team. Their culture is based on an environment where students flourish and faculty self-actualize as master instructors. Finally, they sincerely value all stakeholders and seek to engage families and the community as vital members of Achievement Heights Academy.

The Achievements Heights Academy model consists of an early learners’ school and a school of choice for kindergarten to eighth grade. AHA highly values and respects students for the right they have to the best education. Our program is framed in the caring theory, positive psychology, Lev Vygotsky’s zone of proximation and sociocultural theory, STEAM and effective character education. We know children are powerful and that early learners present a window of opportunity to learn during the most vital and fertile period in a child’s development. In neuroscience, this period is known as synaptogenesis. To maximize learning outcomes for students, they need: (1) teachers who receive appropriate professional development and believe in them; (2) family-school connections; and (3) to be engaged with adults who seek education.

Visit AHA’s site at: http://achievementheights.org/