Autistic Masking in College, with Esperanza Padilla | Spectrumly Speaking ep. 133

Spectrumly Speaking is also available on: Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | SoundCloud

IN THIS EPISODE:

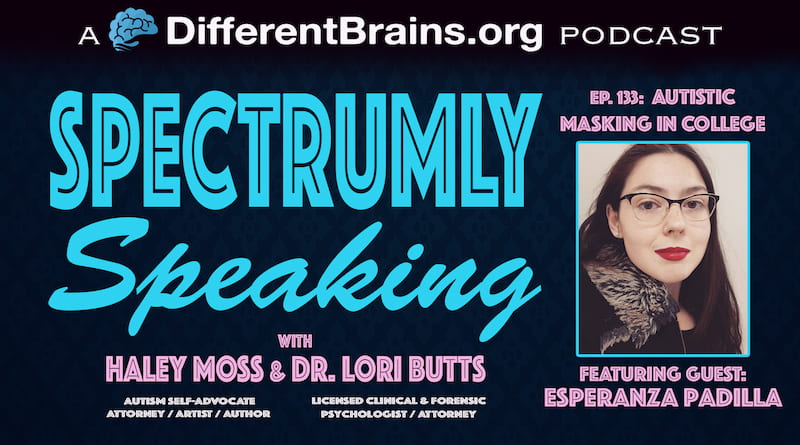

In this episode, hosts Haley Moss and Dr. Lori Butts speak with Esperanza Padilla. Esperanza is a self-advocate who discovered her Autism/ADHD later-in-life, fueling her passion for sociological research on Neurodiversity. Esperanza has extensive experience with self-advocacy to promote inclusion and support of Neurodivergent students at UC Berkeley through her tenure as Executive of Education (2020-2021) and Co-President of Spectrum: Autism at Cal (2021-2022). At Cal Esperanza conducted research investigating the causes/consequences of masking for Autistic adults and how to foster unmasking. Now she is excited to expand on this line of research as an incoming graduate student for a Ph.D. in Sociology at the University of California, San Francisco!

For more about Esperanza’s work:

http://espiology.com/ (site may not yet be active)

Or email Esperanza at: pranza.dia AT berkeley DOT edu

—————–

Spectrumly Speaking is the podcast dedicated to women on the autism spectrum, produced by Different Brains®. Every other week, join our hosts Haley Moss (an autism self-advocate, attorney, artist, and author) and Dr. Lori Butts (a licensed clinical and forensic psychologist, and licensed attorney) as they discuss topics and news stories, share personal stories, and interview some of the most fascinating voices from the autism community.

Spectrumly Speaking is the podcast dedicated to women on the autism spectrum, produced by Different Brains®. Every other week, join our hosts Haley Moss (an autism self-advocate, attorney, artist, and author) and Dr. Lori Butts (a licensed clinical and forensic psychologist, and licensed attorney) as they discuss topics and news stories, share personal stories, and interview some of the most fascinating voices from the autism community.

For more about Haley, check out her website: haleymoss.net And look for her on Twitter: twitter.com/haleymossart For more about Dr. Butts, check out her website: cfiexperts.com

Have a question or story for us? E-mail us at SpectrumlySpeaking@gmail.com

CLICK HERE FOR PREVIOUS EPISODES

EPISODE TRANSCRIPTION:

HALEY MOSS (HM):

Hello, and welcome to Spectrumly Speaking. I’m Haley Moss, an author, artist, attorney, and I’m autistic. I say this probably every single week, but I’m very lucky to get to share the spectrum Lee speaking podcast stage or virtual stage, depending on how you’d like to look at it with possibly the best co host in the game who continually keeps me curious and I keep learning from and I hope that you feel as grateful to have her as I do…

DR LORI BUTTS (LB):

So sweet Haley, I’m Dr. Lori Butts. I’m an attorney and a psychologist. How are you doing?

HM:

I’m doing good. Somehow we are chugging along through what feels like a very exciting Disability Pride Month.

LB:

Great.

HM:

That’s something we haven’t talked a lot about here on the show.

LB:

I don’t think we have, I agree. How’s it going?

HM:

It is good. So there is a new flag this year, which was a really interesting discovery. So Disability Pride Month has its own flag. It’s something that really started with the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which is why we celebrate it in July, in case you are curious, we’re not just riding the coattails of LGBTQ+ Pride Month, we actually chose to lie intentionally. I know that’s something folks probably are like, Wait, is this something that was kind of just continuing? Like no, yeah, ADA month is a big thing. And the ADA anniversary is on I believe, July 26th. That’s 32 this year.

LB:

Wow. That’s really cool.

HM:

Still older than me.

LB:

Yeah. And it always will be.

HM:

I know, I always think about what it would be like if it were a person, because I think of like the fact I have a lot of friends who are probably about 3032 now and I’m like, well, some of them are, you know, getting promoted. They’re getting a new house, they have a baby on the way they might be getting married, they might be getting before it’s like the 32 year olds are kind of doing stuff. It’s young, but it’s not that young, which is why when people say they haven’t had enough time, I kind of just roll my eyes at this point.

LB:

That’s right,when you put in that perspective that’s plenty of time. You’re absolutely right.

HM:

The 32 year olds are keeping busy. Okay, glad we can laugh about that just a little bit. And I know, but how are you? How are you?

LB:

All right, great. Great. Looking forward to today.

HM:

I always look forward to whatever we’re up to. And all the great people that we get to meet here at spectrum Lee and introduce our listeners to so today. Are you ready?

LB:

I am

HM:

You were born ready. Today we are welcoming Esperanza Padilla. And Esperanza is a self advocate who discovered her autism and ADHD later in life, fueling her passion for sociological research on neurodiversity. Esperanza has extensive experience with self advocacy to promote inclusion, and support of neurodivergent students at UC Berkeley through her tenure as executive education and CO president of spectrum autism at Cal. At Cal. Esperanza, conducted research investigating the causes slash consequences of masking for autistic adults and how to foster unmasking. Now, she is excited to expand on this line of research as an incoming graduate student for a PhD in Sociology at the University of California, San Francisco. Welcome to the show.

ESPERANZA PADILLA (EP):

Hey, thank you for having me. This is my absolute pleasure to be able to talk about my journey and a little bit about my work, too.

HM:

I am very excited personally, to learn more about your work. I feel like masking is one of these topics that we talk about quite a bit. And it’s one of these topics that I think the neurotypical and non autistic folks often don’t know nearly enough about. So personally, I am very excited to have you.

EP:

Oh, thank you. And yeah, definitely masking even just for my research. I feel like there’s a lot more you can do. But I’m glad that I’m sort of helping expand on that topic. Because again, it’s something that is so common within neurodivergent communities, but it’s still a little understood still.

HM:

Oh, for sure. And to back us up and probably just give people more of an overview and so they get to know you a little bit. Can you share with us how you became involved in the autism community?

EP:

Sure. So I’m gonna have to rewind several years as things go because I discovered my autism later in life around 2016, 2015. Right around the same time, I was getting diagnosed for ADHD. So at that time, I kind of realized that I was diagnosed earlier on actually with pervasive developmental disorder when I was three tene I was just never really known. So that was news to me. And I began to do some digging at the time. So I was getting this new debt diagnosis of ADHD, I was realizing I had this old diagnosis of, which is now no longer in the DSM of face of developmental disorder, which is now autism. And that’s when I started learning about thoughts as to community online. And from there as like, oh, this explains a lot about me, which, you know, is a very typical reaction for a lot of people who discover their autism or ADHD later in life. But after initial that reaction, I started to learn more about self advocacy and got involved with the Autistic Self Advocacy Network through their autistic campus inclusion in 2017, where I started to really learn more about like the methods and tactics of self advocacy, and I wanted to do it at my community college at the time. But unfortunately, I was due to transfer soon. So that didn’t really materialize as how I wanted to, to happen. But thankfully, when I did transfer to UC Berkeley as a transfer student, I kind of found my home with spectrum autism met cow, which is already a pre established club. But thankfully, as an established club, it’s gone through some stage changes. So now there was a lot more emphasis on moving away from a model of sort of awareness towards neurodiversity celebration, and advocacy. And that’s where I started getting involved more at Cal on the institutional level, first as a general member, and then kind of just came up the ranks as executive unch of education for an academic year, and then co-president for an academic year.

LB:

Wow, can you tell us about what impact you saw through your self advocacy there?

EP:

So one of the major changes, which I’m really thankful that it’s still ongoing is just this emphasis on like space for neurodiverse. Version folks, not just people who are autistic, but also anyone who identifies as neurodivergent. through one of our fireside chat series, where we talk about a topic such as autism and the media representation, we might talk about, you know, about masking at one of our fireside chats. And just as an a disclaimer, if you don’t know what a fireside chat, it’s just an informal chat that you have together in a space and it can be virtual or an in person about some kind of issue. It was actually something I was introduced to in community college, because we’d have fireside chats about immigration status, and things of that nature. And I just sort of translated it to be more geared towards topics of neurodiversity.

HM:

Kind of going right along with your journey, what then decided to make you focus in on masking as a research topic?

EP:

That’s a good question, because it kind of paralyzed paralleled my own journey of self discovery. Because initially, when I started off on my research topic, I was looking at and I did he approach to autism, because you know, it’s something most of us are grown up with a biomedical approach to it being a diagnosable thing, something innate in the body, and not really something that’s seen through a sociological perspective about how autism is addressed. And so as a sociology major at UC Berkeley, I wanted to tackle this subject from a different perspective. So I started thinking about autism as an identity, how it’s built up. And then that sort of segwayed into how does masking work through social interaction, so identity playing, you know, those points and times where we kind of learned a mask, because in my own journey of self discovery, I was learning that I was masking unconsciously as like, Oh, this is weird, and kind of having to dig deep into like, my personal history. And pinpointing, like, certain times when I kind of was influenced to mass covertly, or know very explicitly, and I was interested to learn more about that process. So that’s where I started my my thesis at first. And from there, I also started asking the question of like, well, if we mask is it possible to unmask? Because, like, you know, I know that it’s worked as a sort of tactic for me so far, but it’s also been like, very strenuous, and I don’t want to have to mess my whole life. I’d rather unmasked I like this process of unmasking I’m kind of doing right now. And I wanted to sort of investigate that too. So that’s where I kind of tied in those two topics into my thesis about the causes and consequences of masking, and also what could influence the unmasking process, because I feel like not only do we need to learn more about masking, but also we need to learn more about how can we foster spaces, or ways to make it so we don’t have to mask all the time.

LB:

Can you tell us some of some of what you found through your research into the causes and the consequences of masking?

EP:

Sure, I know, you know, this doesn’t come as a surprise to anyone from the community. But it’s nice to say this explicitly in like a formal thesis, but more masking leads to more burnout. That’s just what happens. You know, it takes a lot out of us to have to put on this mask to fit into neurotypical spaces at our school at our work. And that burnout for us makes it more difficult to actually take care of us and to socialize and do all the things that everyone else does to have happy and fulfilling lives. So it seems kind of obvious for us who have experience with this. But it was important to point that out in my thesis, because it’s not typically addressed in you know, research on autism. And then as for going through the, the causes and consequences my head. Well, definitely, I feel like addressing autism as a disorder was sort of, part of the reason it’s a stigmatized identity, which relates to masking because because even if you don’t know you’re autistic, if you have some kind of weird attribute that is called out, you begin to mask earlier on because you see yourself as being weird, being disordered being abnormal. So regardless of diagnosis status of a participant, that would happen, usually early in their life. And then another consequence of odd autistic masking is that sometimes it doesn’t work out. Like the best way to describe this is like, even though we go in with best intentions to try to fit in the fact that this is a performance to try to come off as someone different, makes people see you as being inauthentic, which then sort of defeats the purpose of masking. So in a way, we’re kind of in a double bind, where like, I feel like I have to do this thing to try to fit in to get the job, you know, to do an interview to get the job, but then someone feels like get the sense that I’m not being my authentic self from covering something up. And then that creates a distance and maybe that actually ends up making so you don’t get the job. So there is this double bind when it comes to masking.

LB:

It makes a lot of sense.

HM:

Yep. I just found myself kind of just nodding along because it’s something that I struggle with too. And for you, what were you finding were the main roadblocks for unmasking?

EP:

So definitely, of the main road blocks really is lack of community and space, and also mentorship. Which is one of the reasons I actually buckled down and emphasize the identity approach. Because I feel like in order to foster those factors of we can’t gatekeeper diagnoses like autism, when trying to advocate for, you know, change in support needs. So it’s important to address it from an identity approach when, you know, allowing people into space to get the resources and information and social support emotional support that they need. Because that way, people aren’t kept out of a community that is created. So, I found that like, honestly, for the most part, it was online communities where people found that they started to belong and understood themselves and felt a lot more comfortable and also knowledgeable because again, this is sort of a process of self discovery for a lot of folks to start to begin to unmask to try to feel like they don’t have to do certain techniques to appear neurotypical or cover up certain attributes about themselves that they think would make them not fit into being neurotypical. And another important part to emphasize is that sometimes it is also very much necessary to bask as a survival tactic. I mean, we have experienced with this with employment, obviously but um In particular, for autistic people of color, masking can be very vital to just like going out in public. You know, police violence is a very real thing. And when you add race and disability on top of that, that increases your likelihood. So it’s very understandable why people feel like they still have to mask in public, especially if you’re an artistic person of color. But when trying to address the issue of unmasking, then we need to start thinking of like questions of how can we foster community, be it in person or virtually. How can we try to connect artistic people with other artistic people through pure or mentorships in college, or in like K through 12? Education? How can we try to create that space? Where we can build that community? And also, how can we try to change our institutional practices? And one interesting thing I found that a lot of participants echoed was the need for artistic representation, not just in media, I mean, that’s important. But like, everywhere, there’s a decision being made. I’m sure you’ve heard of this thing before. But if you’re not at the table, then you’re the dinner or the lunch or something like that. But what that what that saying is meant to say is like, you need to be at the place where decisions are being made in order for change to happen. And like having like someone to consult with honor, diversity, on the practices of an institution on a hiring program is really inset essential. And ideally, these people should be getting paid as well, much as you would pay someone to try to make workplaces less hostile to women. So that was an interesting finding, I found for my participants, because I did echo the sentiment that autistic people should be consulted about changes that need to be made to make things more inclusive at work or at school.

LB:

That’s amazing. That’s really great. How can our listeners learn more about your work?

EP:

So um, that is a good question, because I’m sort of in the process of publishing it. But it’s not quite there. And I think I’m kind of in the works with a website. But again, that’s not quite there. This is, this is the summer of work in progress is for me, because I’m just getting this work done because I did this in 2020 and 2021. I just need a break after that. So I didn’t pursue publishing until this year. Which, you know, c’est la vie. But it’s in the process, which is good. And I think the, at the moment, the best way to get a hold of this work, which is to be to email me. Did you would it be okay to plug my email?

LB:

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely.

EP:

Okay. So for the time being, I’ll use my Berkeley email so that you know, you know, it’s not just some random person at least I’m affiliated with an institution so bear with me because it’s not the easiest email either. It’s: pranza.dia@berkeley.edu. And then the website again, you’re not going to find anything at the moment. But maybe, honestly, probably by the time this podcast comes out, there will be something which is great. So perfect timing. The website I’m going to have is espiology.com. It’s a play on my nickname, SP and sociology. So that’s the best I can come up with. And yeah, it thankfully, by the time this podcast comes out, there’ll be something but it is kind of embarrassing reveal how much your work work in progress. My publishing life is.

LB:

Um, you’re not alone on that. That’s pretty typical. It’s a lot of work.

EP:

Yeah. But that’s what 2022 is just a lot of work.

HM:

So we want to do a little bit of a segment have a more candid conversation as well about where this whole conversation about masking and unmasking really fits into self discovery for and how we advocate for ourselves, especially for college students. I know that for college students, whether you’re neurotypical neurodivergent, disabled or non disabled, it’s really a huge time of self discovery and figuring out what you want in life and who you are, that kind of leads us to wanting to talk about this when it comes to Autistics and whatnot, and where that unmasking may be coming into place. I’m not sure where I want to start this conversation. But I do think college, at least for me, was the very first time that I really became aware of the neurodiversity movement, that I realized that I wasn’t the only autistic person out there. And I had spent my entire high school career essentially, masking and camouflaging trying to just not get bullied, trying to make friends, and still not doing very well at it to be quite honest. And college felt like this fresh start. And I remember going on this dei retreat, and disability and neurodiversity were barely even addressed. And I felt this compulsion to really get that conversation moving.

EP:

Yeah, definitely, you’re on point with like college being a place of self discovery. Oddly enough, the journey of self discovery for autistic folk or other inner diversion Folk is very similar to how the LGBTQ Q movement is when it comes to, you know, your experiences of discovering your sexuality, and your gender identity. So they kind of all take place in the similar space of college. And it’s interesting that how much we can parallel with talking about neurodiversity, and presenting it as how the LGBTQ movement has been with the different, you know, identities of sexuality of gender identity. I feel like there’s a lot we can learn from that movement and how we address like, you know, teaching about neurodiversity, and approaching it from a more civil rights perspective. Because in that respect, we could actually, you know, at the college level, start to do more advocacy work, and ideally, at the more political legislative level, also start passing some laws to help support and I, you know, recognize the needs of people who are divergent.

HM:

I also think with college students that they don’t realize how much power they actually have. I think that there’s this kind of belief that because you’re a student, there isn’t really much that you can do. I don’t know why I feel this way about community. And I think it’s something that I felt because I felt defeated in college because the only autism organization on campus was to provide respite care to parents in the community. So it was not a Autism Speaks chapter it was something completely independent, but it was still something that I just didn’t feel like I was the I felt like I was the autistic person. And I remember the disabilities like Resource Center at my college had a support group of auto for autistic students. And it was led by some neurotypical peer facilitator, and nobody felt comfortable opening up. And I remember after the one time I went, there was a senior girl, I was probably a freshman or sophomore, and she was in a sorority, and going to a big university in the south, being a sorority girl is like a whole, basically, masterclass, and masking, essentially, for lack of a better word, that how you dress what you act like, it’s all very prescribed, almost, I think, even for the neurotypicals. I don’t know, I was not in a sorority. So if you’re in a sorority, and you’re listening to this, I’m so sorry. But I was very fascinated by this autistic senior girl who was in a sorority, and I wanted to know, like, did they accept her? Was she being herself and all of these different things, and it was truly fascinating for me, and I wish that we had had better community and I actually stayed in touch with her too. And then when I got to law school, we had no disability advocacy org or anything of that nature. We ended up getting all these great disabled law students resources after I graduated nationwide and at my former law school.

EP:

Yeah, you definitely bring up a good point about feeling like sometimes as an undergrad, it feels like you can’t do change. But I don’t know. I’m speaking from a place of privilege because I went to UC Berkeley and it was like, you know, the epicenter of the Free Speech Movement. The fact of the matter is like in truth, there is a lot of power you can have as an undergrad, but it really does matter on like how many people you can reach you know, the organizational capacity of like creating a community or a program or service. For example, I resonated a lot with with your story about college reminded me when I was in community college, and there’s a lot of good things about community college do not get me wrong. I love Community College. I will tended till my dying breath. But one of my, you know, big pet fees was like it was so hard at my community college to talk about disability law, no alone neurodiversity. And that’s part of the reason why I couldn’t complete my goal of wanting to create like an advocacy org at a community college. And that’s why that had to rate wait until I got into Berkeley, which was a little bit more open a whole lot more organized ational capacity, because Spectrum was already existing. And so yeah, it really it does. advocacy work at the college level, can be really difficult. But it’s also possible, it just, it’s really about getting that group together, and putting something together. And yeah, it’s a lot of hard work if you’re starting from scratch, but it is possible. So I do want to give, you know, college students some hope. And again, we’re living in a digital world and artistic people are more connected now more than ever, and it’s much easier to share, you know, tips and to connect with people. So like being able to connect with people who already have an established organization who’ve already gone through the motions and have a process can help a lot and like establishing your own the organization.

LB:

Yeah, I think that college students have a lot more energy. And they certainly, they certainly, like what you’re saying is Francaise now, with the internet and with other different movements that can show can show how it’s done. And you can model you know, if your local area doesn’t have it, you there’s other models that you can follow. And there’s, I mean, we’ve spoken to so many people on Spectrumly here that are just so accessible, like you are to, for our listeners to reach out to and for guidance and mentorship and things like that to help to help in a in a process or progress, whatever they want to want to do in their local communities or just for themselves, you know, even if they don’t want to start a movement just for somebody who just wants to navigate living in college and being autistic. You know, there’s so many resources and so many wonderful people that seem to be accessible and willing to chat and, and encourage, like both of you.

EP:

Yeah, and before I, you know, forget or move on to the next point. But um, I’ve definitely had personal experience with this myself, even as a leader with spectrum autism at Cal, being connected to a graduate student at UC Davis, who’s autistic and who was the chair of their Aggie neurodiversity, community general meetings, and learning a lot from him and him learning a lot for me, I hope so I don’t know, I hope he did. Because we’ve had informal conversations over zoom. And just to kind of get a sense of like, what their organizations are doing. And I was impressed by how the neurodiversity organization at UC Davis created a space for advocacy. So you had self advocates and allies doing sort of policy work. And then you had a space for community, which is for neurodiverse, neurodivergent people to come together to talk and to share their experiences. And I actually started advocating for that at my board meetings, and my fellow board members, that spectrum actually ended up listening to me and say, hey, that’s actually a good idea. So we ended up creating an officer for advocacy, an officer for neurodiversity sort of emulate with the Aggie. The Aggies are doing at UC Davis with their neuro diversity groups. So that’s one example of how it’s possible to learn and model off of each other, which is really important in establishing your own organization. Even if you already have an organization, it’s important to learn from what’s working from others, or did you a better job?

LB:

Right, right. That’s — exactly.

HM:

I think something else that was really powerful for me as a young person is learning not to feel ashamed or when I get it wrong. I feel like there’s kind of this social pressure constantly, especially when you’re young and you are somewhere new as so many college students are that they’re really on their own for the first time. And they get a lot quote unquote wrong by societal standards because there’s not additional support people, there’s just different things that come with being on your own, or just not understanding certain adult, quote unquote, social situations, and not having to apologize for everything that I ever did or felt or got wrong, quote, unquote, was really big, I think in the unmasking process for me.

EP:

Oh, yeah, I definitely resonate with that. Because I feel like I’ve definitely was more high strung and apologetic, I don’t know, like several years ago, as a opposed to what I am right now. And part of that is, along with aging is also just learning how to identify what matters and what doesn’t really matter. And becoming a bit just more more more confident in who I am. And figuring out who I am, makes it a lot easier to just sort of unmask little by little, even though I have like, all this years of pent up masking, being able to unravel it, and acknowledged my mistakes, and no longer having a meltdown over it has been made a phenomenal difference for me.

HM:

That’s too and I do realize there are plenty of situations to where I do mask, and I realized that some of that’s my own internalized ableism survival skills or just not knowing how to navigate a situation. And I also do feel like so much pressure goes on us to make non autistic neurotypical people especially feel more comfortable. And I’m beginning to realize I don’t always have to do that work for them.

EP:

Yeah, yeah, exactly. Especially, you know, when it’s not a high stakes situation, and you can be a bit more of yourself, which is a game changer when because, like, in the past, I’ve, like, kept masking all the time. And like that led to more instances of burnout. And yeah, once you learn, there’s some situations which are, are safe free for you, it helps a lot.

HM:

What are you feeling Dr. Butts?

LB:

I feel like I don’t have a real place in this conversation, just because it’s an experience that both of you have that I don’t have. But I I enjoy hearing about it. Because I think it’s important. And and I can empathize about having burnout because of masking. And I think the other thing that I can relate to it is, you know, you have, which is probably a bad example, and hopefully not offend it offensive, but like, you know, you have your different roles in life, and you’ve got your professional role and your, you know, your home rolling your and, and so having to kind of always be on what you know, like, that’s how I kind of imagined what masking is like for. And it is exhausting to have to be on all the time.

HM:

It’s a pretty accurate description of that you’re just always on I feel like being autistic a lot of the time when people ask me what that experience is like, they expect me to talk about all the sensory stuff and everything and I just go, most of the time, I’m tired. And I realized that’s why I’m tired. It’s like having a 24/7 customer service persona, where even when the people are screaming at you, you still have to nod and smile and right. Literally everything and not just for that nine to five, but in 24/7. Right. Yeah, that’s the way that I will describe it. If people really don’t know anything is it’s like having a permanent customer service person.

EP:

That’s a really good example. I like that.

LB:

Yeah, I did to

HM:

Someone else taught that to me, and I kind of just rolled with it. And they were like, because it was something that came out of a joking conversation with another autistic friend. We’re like, Yeah, it’s kind of like working in customer service. I’m like, Yeah, sounds about right. Because you know, they’re doing the same thing, because they’re not, they don’t want to deal with you.

LB:

Exactly.

HM:

And they’re just like, trying to like make eye contact that and nod and smile. And like when you’re the one who’s in a bad mood. They’re like, Yes, ma’am. It’s kind of okay. They’re probably like, I want to kill this girl. Like she needs to shut up. And they can’t say it even though they want to because it’s socially inappropriate and has consequences. I have lots of feelings. If there are any autistic people who do work in retail or customer service, please let us know your experience.

EP:

Oh, yeah. I imagine that’s a real thing. And I have no doubt there’s at least a huge number who’ve had experience in the store currently doing it right now.

HM:

Happily, I feel like that’s the ultimate like masking Trifecta almost of like, job, customer service, social norms, autism, people who are never happy with you. It sounds exhausting. Yeah, I’m glad that’s not an experience I have at this point. I do have to sometimes manage people getting very stressed but that’s about it. Do we have any words of wisdom that we want to part with in our little unmasking journey, especially for the young folks who are still figuring it out?

EP:

Yeah, that’s a good question. I’ll have to think about that. Because I feel like you know, words of wisdom, oh, I’m going to influence young people. Now. It seems like would you pull younger you? Oh, my goodness. seems so obvious and funny. Everyone told her she’s autistic for one. Because she didn’t know. But other than that, I would have told her to get connected with people online. You know, start networking with people on Twitter are, there’s there’s dozens of Facebook groups. Start talking to people who are, are artistic or who are doing work, learning about them. And you know, from learning about them, not only will you learn more about yourself, but you’ll learn more about what you can do you learn about advocacy, you’ll learn about, you know, the different tactics you can take to make social change. I think, you know, that’s an important bit of wisdom is just learning how to, to networks, because that way, finding others and finding community, that’s what’s going to make a difference not only in your life, but like hopefully, in the lives of many other people in the future, too.

HM:

I think that’s a great thing as well. And I think that almost just about wraps up our conversation for today. And I’m really grateful that we had you today. Esperanza, I truly appreciated getting to learn from you. And I think the rest of us here at Spectrumly. And our listeners will truly appreciate your insights as well. As for the rest of us, be sure to check out differentbrains.org and check out their Twitter and Instagram @DiffBrains and don’t really talk to them on Facebook. If you’re looking for me, please say hello at Haleymoss.com. Or feel free to connect with me on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram or LinkedIn as well. I always love to hear from you. And hope to keep this moving and to hopefully continue unmasking together.

LB:

And I can be found at CFIexperts.com. Please be sure to subscribe and rate us on iTunes. And don’t hesitate to send questions to spectrumlyspeaking@gmail.com. Let’s keep the conversation going.

Spectrumly Speaking is the podcast dedicated to women on the autism spectrum, produced by Different Brains®. Every other week, join our hosts Haley Moss (an autism self-advocate, attorney, artist, and author) and Dr. Lori Butts (a licensed clinical and forensic psychologist, and licensed attorney) as they discuss topics and news stories, share personal stories, and interview some of the most fascinating voices from the autism community.